The results presented below are based on a questionnaires distributed to 69 participants from the different Working Groups. The surveys, conducted using Google Forms, was open from February 7th to March 9th, 2025.

Click to jump to the desirable working group results.

PM2.5 and PCN Working Group

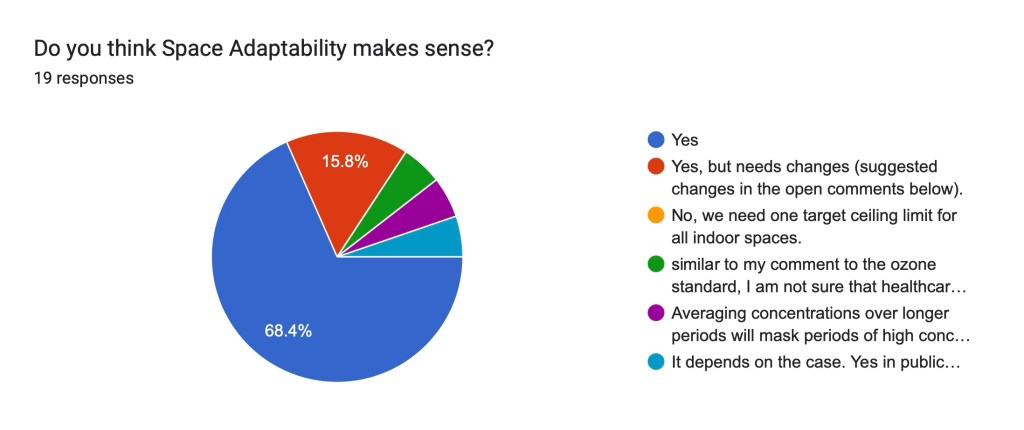

1st Question

The working group on PM2.5 and PCN, with 19 out of 47 registered members participating, revealed a generally positive view towards “Space Adaptability,” with 66.7% agreeing and 16.7% agreeing with modifications. However, concerns were raised regarding the practical implementation and effectiveness of this concept. Participants highlighted the context-dependent nature of its applicability, favoring it for public buildings while questioning its feasibility in dwellings, particularly those relying on natural ventilation. The necessity of mechanical ventilation with filtration was emphasized, alongside the potential for increased costs and reduced energy efficiency due to dynamic damper systems required for adaptable airflow. Another critical point raised was the potential for averaging concentration measurements to obscure short-term, high-exposure events, such as those occurring during specific periods of a school day, thus limiting the accuracy of exposure assessments.

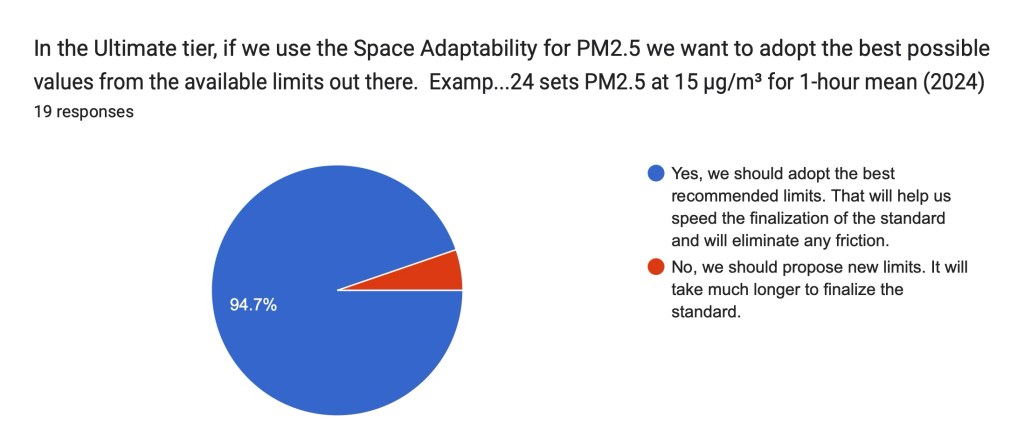

2nd Question

The working group exhibited a strong consensus, with 94.4% of participants agreeing that the “Ultimate” tier’s Space Adaptability framework should utilize the “best possible values” from existing PM2.5 limits:

- WHO sets PM2.5 at 5 μg/m³ for 1-year mean (2021)

- WHO sets PM2.5 at 15 μg/m³ for 24-hour mean (2021)

- N/A sets PM2.5 at 15 μg/m³ for 8-hour mean (N/A)

- Morawska et al., 2024 sets PM2.5 at 15 μg/m³ for 1-hour mean (2024)

This demonstrates a clear preference for leveraging established, rigorous standards. While the vast majority favored adopting these optimal, readily available limits, one participant dissented, advocating for the development of entirely new, potentially more stringent limits. This lone voice highlighted a desire to push beyond current benchmarks, although the overwhelming majority prioritized the immediate implementation of the strongest existing standards.

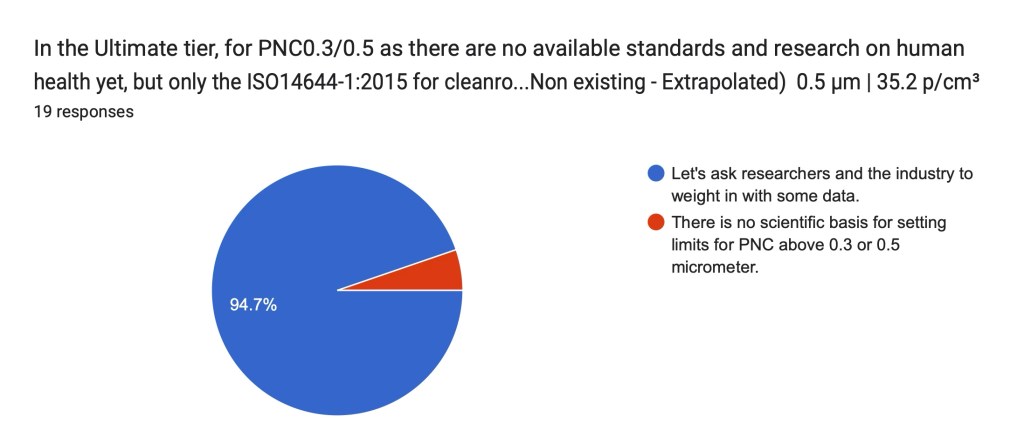

3rd Question

The working group’s discussion regarding the “Starter” tier’s Space Adaptability for PM2.5 revealed a strong majority (83.3%) in favor of adopting the “best interim target limits” from existing standards:

- Norway sets PM2.5 at 8 μg/m³ for 1-year mean (2020)

- WHO sets PM2.5 at 25 μg/m³ for 24-hour mean (interim target 4 – 2021)

- N/A sets PM2.5 at 25 μg/m³ for 8-hour mean (N/A)

- N/A sets PM2.5 at 25 μg/m³ for 1-hour mean (N/A)

This indicates a pragmatic approach, aiming to implement achievable, yet still protective, measures as a starting point. However, a notable minority of three participants dissented, advocating for the development of new, potentially interim limits. This divergence suggests differing perspectives on the balance between immediate implementation and the potential for tailored, potentially more lenient, standards within the “Starter” tier.

4th Question

The working group, when addressing PNC0.3/0.5 within the “Ultimate” tier, demonstrated a strong consensus (94.4%) to pursue a data-driven approach, recommending that researchers and industry provide input to establish ceiling limits. Recognizing the absence of established health-based standards for these particle sizes, the group proposed extrapolating ISO 14644-1:2015 cleanroom levels (ISO 8 and 9) and conducting tests in various settings to inform limit recommendations. The initial focus would be on evaluating filtration efficiency and detecting submicron aerosols, rather than direct health impacts. A single dissenting voice expressed skepticism, arguing that there is no scientific basis for setting limits for PNC above 0.3 or 0.5 micrometers, highlighting a fundamental disagreement regarding the viability of setting any limit at those particle sizes.

Open Comments

The working group’s comments on Space Adaptability and PM2.5/PNC limits revealed a range of perspectives and concerns. Participants highlighted the contextual nature of Space Adaptability, favoring it for public buildings but questioning its applicability in dwellings, especially those with natural ventilation. The need for mechanical ventilation with filtration was emphasized, along with the potential cost and energy efficiency implications of dynamic damper systems. Concerns were raised about the prevalence of naturally ventilated dwellings, particularly in regions like Spain. The inclusion of manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and the separation of hospitality settings into restaurants and hotels were suggested. Some participants advocated for consistent limits across tiers, questioning the idea of less stringent “Starter” tier standards. The complexity of IAQ in schools and hospitals was acknowledged, with a focus on sensitive populations and diverse pollutant sources. A strong sentiment emerged for moving away from μg/m³ measurements, with a preference for particle count metrics, reflecting a focus on submicron particles. The importance of field testing and potential adjustments to limits was also highlighted, with concerns about the impact of urban pollution and device memory limitations on long averaging periods.

Carbon Dioxide Working Group

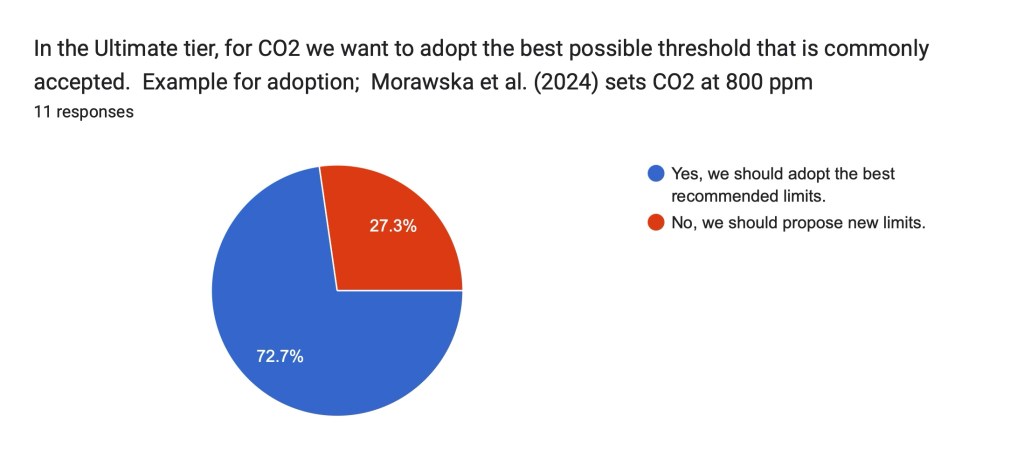

1st Question

The carbon dioxide working group, with 11 out of 30 registered members participating, showed a strong majority (72.2%) in favor of adopting the “best possible threshold” for CO2 in the “Ultimate” tier:

- Morawska et al. (2024) sets CO2 at 800 ppm

This indicates a clear preference for utilizing established, well-regarded standards. However, a dissenting minority of three participants advocated for the development of new, potentially more stringent or tailored limits, suggesting a desire to move beyond existing recommendations.

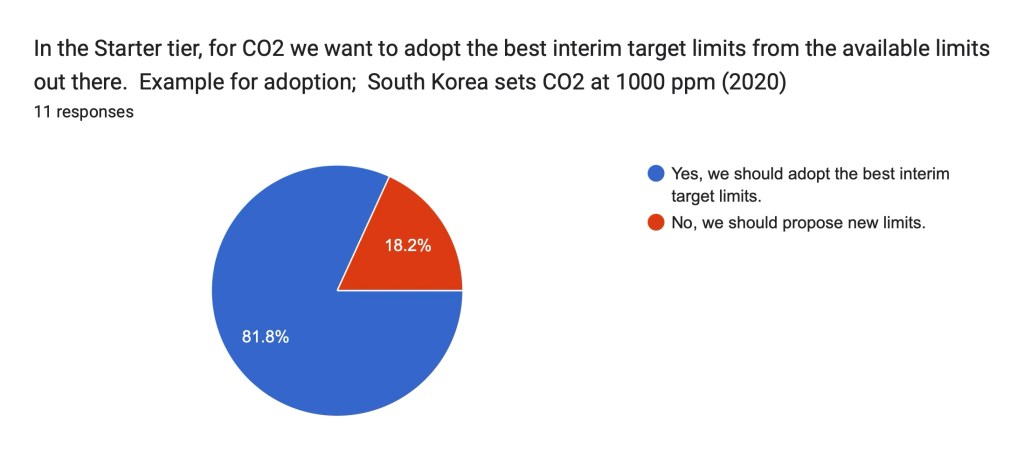

2nd Question

The working group, when discussing CO2 limits for the “Starter” tier, demonstrated a strong majority (81.8%) in favor of adopting the “best interim target limits” from existing standards:

- South Korea sets CO2 at 1000 ppm (2020)

This indicates an approach, prioritizing the use of established, achievable targets for initial implementation. However, two participants dissented, advocating for the development of new, potentially different interim limits, suggesting a desire to explore alternative standards within the “Starter” tier.

Open Comments

The open comments from the carbon dioxide working group highlighted several crucial points regarding indoor air quality (IAQ) and CO2 limits. A significant emphasis was placed on recognizing IAQ as a vital accessibility and inclusion factor, particularly for individuals with chronic health conditions. Reports cited the disproportionate harm caused by airborne pathogens in poorly ventilated indoor spaces, underscoring the urgent need for accessible IAQ standards in public areas. The group acknowledged existing standards like ASHRAE 241 and Lidia Morawska’s 2024 blueprint, advocating for their consistent application and potential tightening of limits.

Members stressed the importance of context-specific CO2 limits, arguing that a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate. They pointed out that factors like building type, occupancy, and individual health conditions should be considered when setting standards. For example, they suggested that environments like aged care facilities and hospitals, where vulnerable populations reside, may require stricter limits than classrooms. Furthermore, the group emphasized the need for risk assessments to inform limit recommendations, rather than relying on arbitrary values. They also highlighted the relevance of the difference between outdoor and indoor CO2 concentrations.

Economic considerations were also brought to the forefront, with some members proposing a “payment for air quality” system. This concept suggests that those seeking higher IAQ standards should contribute financially, thereby incentivizing improvements and addressing the resource demands of enhanced ventilation and filtration. Additionally, concerns were raised about the economic implications of stricter IAQ standards for less developed countries, advocating for equitable resource distribution and potential subsidies for IAQ improvements.

Carbon Monoxide Working Group

1st Question

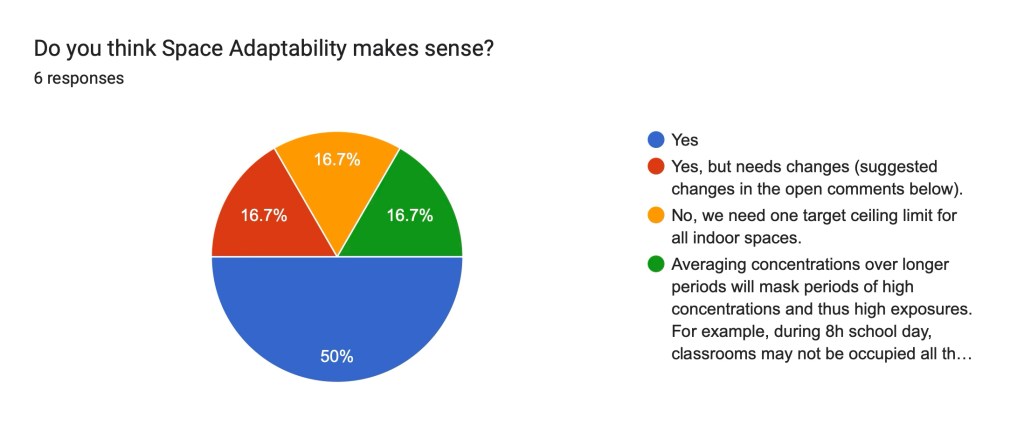

The carbon monoxide working group, with 6 out of 13 members participating, showed a divided opinion on the concept of “Space Adaptability.” While 50% agreed to adopt the best limits, a significant portion disagreed. Three members expressed concerns: one advocating for changes to the concept, another arguing for a single, universal ceiling limit for all indoor spaces, and the third highlighting the issue of averaging concentrations over long periods, which could mask short-term, high-exposure events. This division indicates a need for further discussion and clarification regarding the implementation of Space Adaptability for carbon monoxide, particularly regarding the potential for masking exposure peaks and the feasibility of a uniform limit.

2nd Question

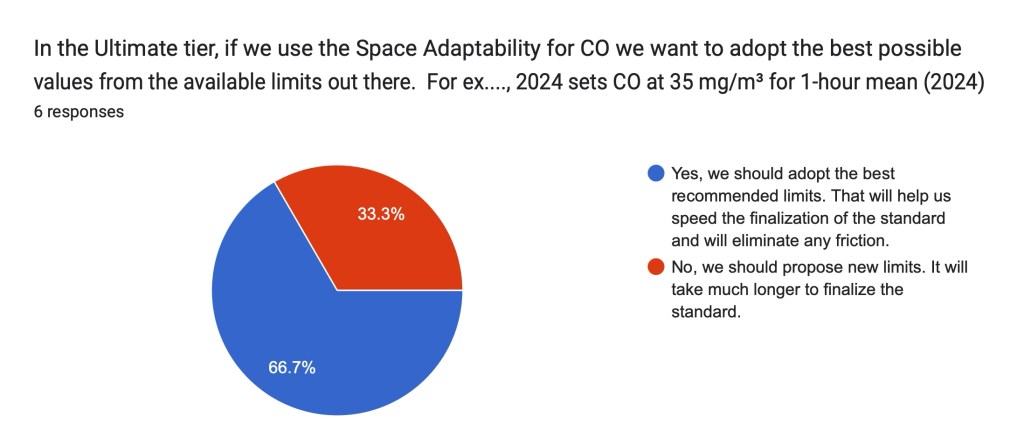

The carbon monoxide working group, with a majority (66.7%) of participants agreeing, favored adopting the “best possible values” from existing limits within the “Ultimate” tier’s Space Adaptability framework.

- France sets CO at 30 mg/m³ for 1-year mean (2007)

- Poland sets CO at 3 mg/m³ for 24-hour mean (2008)

- Germany sets CO at 10 mg/m³ for 8-hour mean (2021)

- Morawska et al., 2024 sets CO at 35 mg/m³ for 1-hour mean (2024)

This approach demonstrates a preference for leveraging established, rigorous standards. However, two members dissented, advocating for the development of new limits. This dissenting view, while representing a minority, highlights a desire to potentially exceed current benchmarks. Importantly, it was acknowledged that pursuing new limits would significantly prolong the process of finalizing the standard.

Open Comments

The open comments from the carbon monoxide working group revealed several key concerns and recommendations. Participants emphasized the need to expand the scope of “Space Adaptability” to include manufacturing facilities and warehouses, and to differentiate hospitality settings into restaurants (1-hour classification) and hotels (8-hour classification) for more accurate assessment. A strong sentiment emerged for a single, universal CO limit to simplify implementation and avoid public confusion, though establishing a consensus on this limit based on scientific evidence was acknowledged as crucial. Concerns were raised about the significant discrepancies between existing national limits, particularly highlighting the wide gap between France and Poland’s standards. The group recognized the challenge of finding a compromise that effectively addresses both indoor air quality and long-term CO exposure, indicating a need for thorough research and debate to establish a defensible and globally applicable limit.

Formaldehyde Working Group

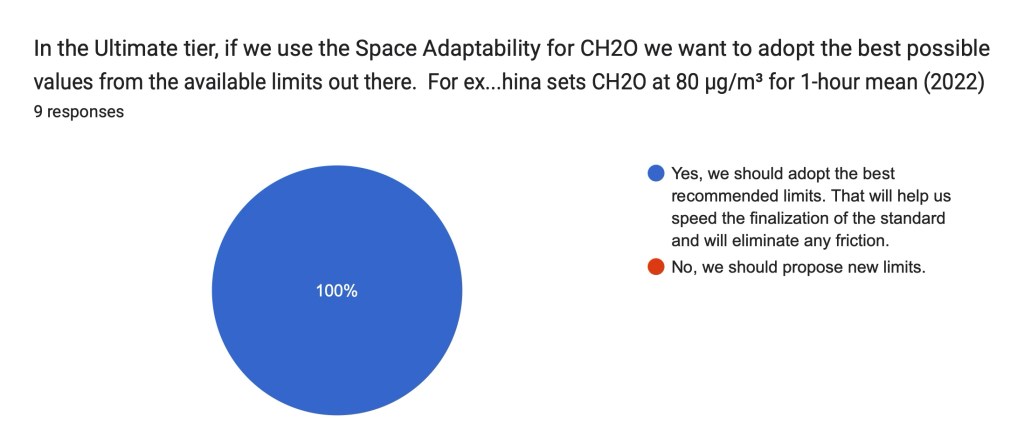

1st Question

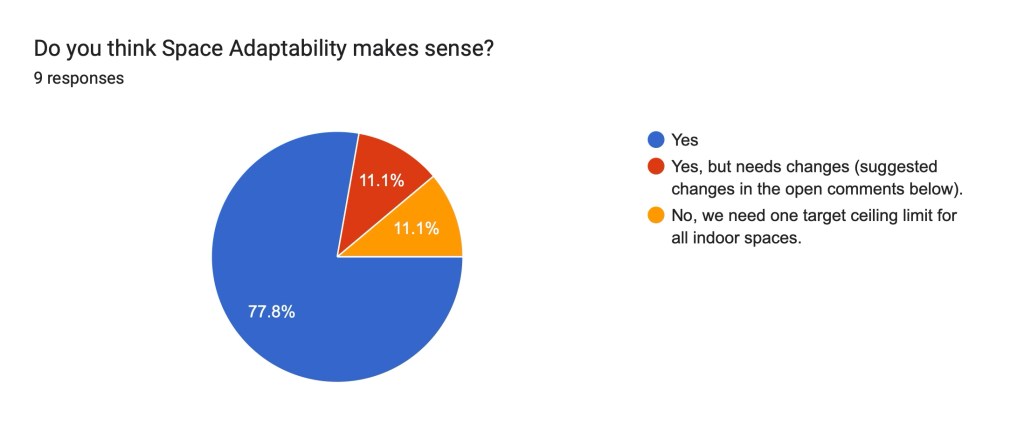

The formaldehyde working group, with 9 out of 19 members participating, demonstrated a significant majority (77.8%) in favor of “Space Adaptability,” indicating a preference for context-dependent formaldehyde limit setting. However, two dissenting members expressed a desire for a unified approach, advocating for a single, target ceiling limit applicable to all indoor spaces. This divergence highlights a tension between the need for flexible, adaptable standards and the desire for simplicity and consistency in formaldehyde exposure limits.

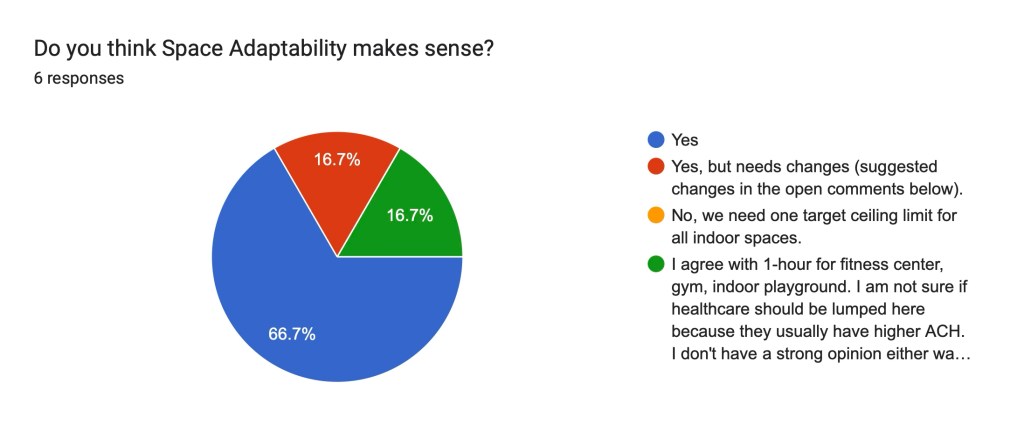

2nd Question

In a rare display of complete consensus, the formaldehyde working group, when considering the “Ultimate” tier’s Space Adaptability for CH2O (formaldehyde), achieved 100% agreement on adopting the “best possible values” from existing limits.

- UK sets CH2O at 10 μg/m³ for 1-year mean (2019)

- Poland sets CH2O at 20 μg/m³ for 24-hour mean (2008)

- Hong Kong sets CH2O at 30 μg/m³ for 8-hour mean (2003)

- China sets CH2O at 80 μg/m³ for 1-hour mean (2022)

This unanimous decision signifies a strong alignment among members regarding the selection and implementation of established, rigorous standards for formaldehyde within this framework, marking a significant departure from the divided opinions observed in other areas of discussion.

Open Comments

The open comments from the formaldehyde working group highlighted several key areas of concern and proposed refinements. Participants emphasized the need to extend the concept of “Space Adaptability” to include manufacturing facilities and warehouses, and to differentiate hospitality settings, classifying restaurants for 1-hour exposure and hotels for 8-hour exposure. Concerns were raised about the cumulative effects of gaseous pollutants like formaldehyde, emphasizing the importance of initial exposure limits and the potential for harmful buildup in the human body. Additionally, the group acknowledged the challenge of setting realistic formaldehyde limits, citing the example of China, where limits are set high due to the lack of stringent policies to reduce formaldehyde emissions from building materials. This suggests a need for a nuanced approach that considers both health impacts and practical implementation challenges.

Ozone Working Group

1st Question

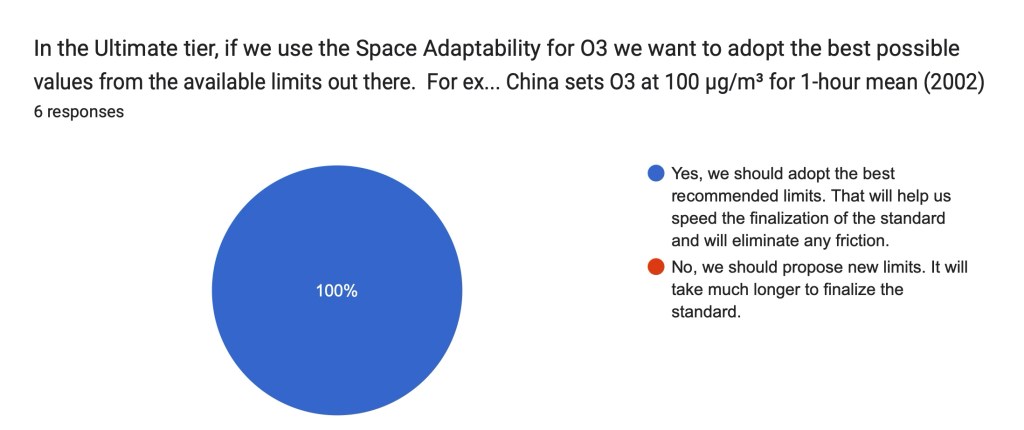

The ozone working group, with 6 out of 15 members participating, demonstrated a majority (66.7%) in favor of “Space Adaptability,” indicating a preference for tailored ozone limits based on specific environments. However, two members advocated for a uniform ceiling limit across all indoor spaces, expressing a desire for simplicity and consistency. Additionally, one participant proposed a 1-hour limit for fitness centers, gyms, and indoor playgrounds, while raising concerns about the appropriateness of including healthcare facilities within this category due to their typically higher air change rates, highlighting the potential for discrepancies within that 1-hour classification.

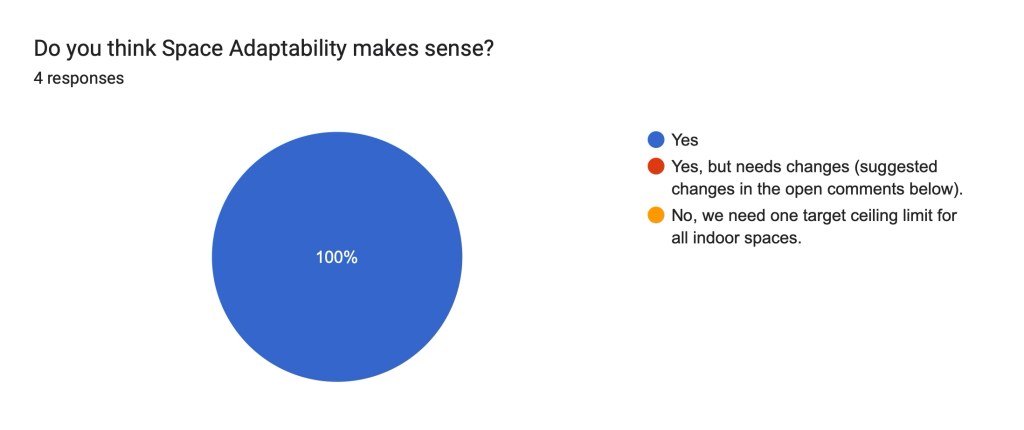

2nd Question

The ozone working group achieved unanimous agreement, with 100% of participants supporting the adoption of the “best possible values” from existing limits within the “Ultimate” tier’s Space Adaptability framework for ozone (O3).

- India sets O3 at 100 μg/m³ for 1-year mean (2009)

- Thailand sets O3 at 100 μg/m³ for 24-hour mean (2022)

- Lithuania sets O3 at 30 μg/m³ for 8-hour mean (2007)

- China sets O3 at 100 μg/m³ for 1-hour mean (2002)

This complete consensus indicates a strong preference for utilizing established, rigorous standards for ozone control in this tier, showcasing a clear alignment among members regarding the implementation of existing optimal limits.

Open Comments

The open comments from the ozone working group highlighted several key considerations for establishing effective standards. Participants emphasized the need to expand “Space Adaptability” to include manufacturing facilities and warehouses, and to differentiate hospitality settings into 1-hour (restaurants) and 8-hour (hotels) classifications. There was an agreement on adopting existing limits for now, but concerns were raised regarding the high ozone standard in China for 1-hour means, which was considered illogical compared to 8-hour standards. Members suggested including units in ppb alongside μg/m³ for clarity, given ozone’s gaseous nature, and requested comprehensive references within the spreadsheet for transparency. The group also acknowledged the importance of considering UL’s conservative indoor emission standards for equipment, which are significantly lower than some proposed limits. Additionally, the impact of high outdoor ground-level ozone in certain geographic areas was highlighted, emphasizing the need to account for infiltration through open windows. These comments collectively underscore the necessity for a nuanced approach that integrates diverse factors, including geographical variations, equipment emissions, and established standards, to develop robust and relevant ozone limits.

Nitrogen Dioxide Working Group

1st Question

The nitrogen dioxide working group, with a very limited participation of only 4 out of 17 registered members, reached an agreement (100%) on the applicability of “Space Adaptability.” Despite the low participation rate, this complete consensus suggests a strong, albeit narrowly represented, belief in the necessity of tailoring nitrogen dioxide limits to specific indoor environments.

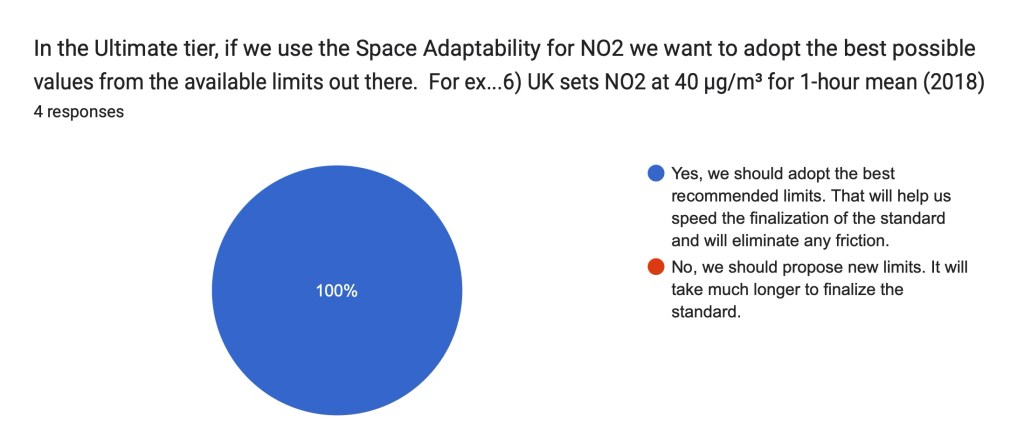

2nd Question

With a very small participation of 4 out of 17 registered members, the nitrogen dioxide working group achieved complete consensus (100%) on adopting the “best possible values” from existing limits within the “Ultimate” tier’s Space Adaptability framework for NO2.

- WHO sets NO2 at 10 μg/m³ for 1-year mean (2021)

- Canada sets NO2 at 21 μg/m³ for 24-hour mean (2015)

- Singapore sets NO2 at 40 μg/m³ for 8-hour mean (2016)

- UK sets NO2 at 40 μg/m³ for 1-hour mean (2018)

This common decision, though based on limited participation, demonstrates a clear preference for utilizing established, rigorous standards for nitrogen dioxide control in this tier.

Open Comments

The primary concern raised by participants in the nitrogen dioxide working group centered on the limitations of low-cost NO2 sensors. Specifically, they highlighted the potential for limited accuracy and cross-sensitivity with ozone (O3). This raised a critical issue: the possibility of very low NO2 limits triggering false positive notifications due to inherent sensor inaccuracies. This comment underscores the need for careful consideration of sensor technology limitations when establishing NO2 standards, particularly when aiming for highly sensitive or stringent limits.

Radon Working Group

1st Question

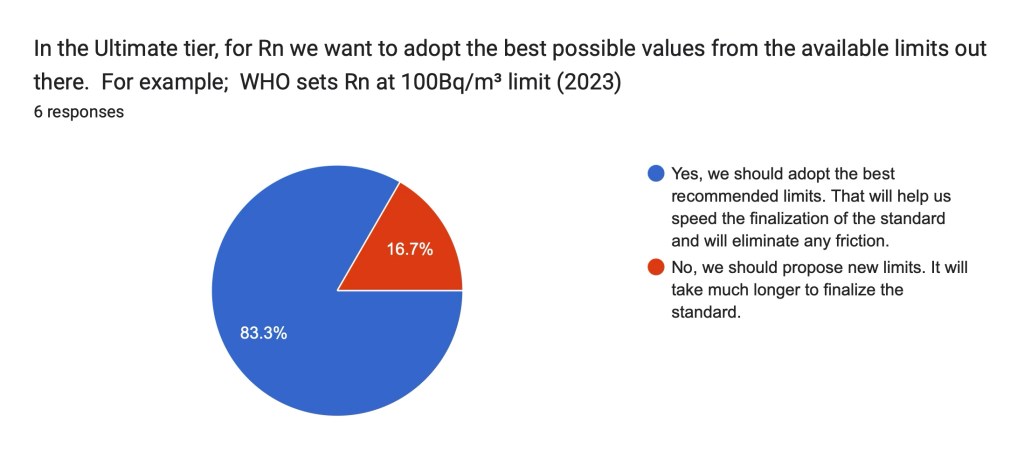

Of the 10 members initially registered for the radon working group, 6 participated in the discussion regarding radon limits within the Ultimate tier.

- WHO sets Rn at 100Bq/m³ limit (2023)

5 of the 6 participating members agreed. However, one expert expressed a desire for an even more stringent limit, advocating for a value below the 100 Bq/m³ threshold.

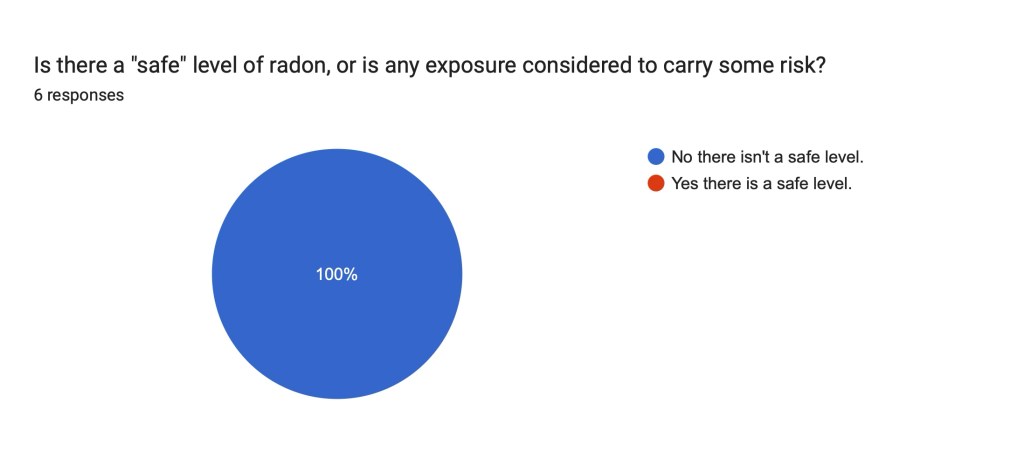

2nd Question

The radon working group, with a common agreement from all participating members, concluded that there is no “safe” level of radon exposure. This consensus reflects the understanding that any exposure to radon carries some degree of risk, reinforcing the importance of minimizing radon levels in indoor environments.

3rd Question

The radon working group discussion revealed diverse perspectives on why radon action levels differ across organizations and countries. Participants cited a range of factors, including variations in risk assessment interpretations, differing priorities between stringent precautionary measures and economic feasibility, and the influence of building and climate factors on mitigation challenges. Regulatory approaches and political decisions also play a significant role, with some countries prioritizing legally binding limits while others offer recommendations. Several members highlighted the impact of construction differences and political will, suggesting that technical and economic difficulties, rather than solely prioritizing end-user protection, drive some discrepancies. Others emphasized the role of risk perception and the degree to which governments prioritize public health versus economic considerations, with one participant asserting that varying levels reflect different levels of governmental concern for citizens’ well-being. A strong consensus emerged for establishing a technically coherent, universally protective limit.

4th Question

The radon working group emphasized the importance of both short- and long-term radon measurements for accurate indoor assessments. Short-term tests were recommended for initial screenings and post-mitigation evaluations, while long-term tests, ideally lasting at least 90 days and conducted during the heating season where applicable, were deemed essential for determining annual average concentrations. Participants stressed the need to maintain typical occupancy conditions during testing, or closed-building conditions if unoccupied, and advocated for retesting buildings at regular intervals to ensure mitigation systems remain effective. Opinions varied on retesting frequency, ranging from annual checks after major building changes or extreme weather events to retesting every two to five years, with some suggesting less frequent retesting if continuous digital monitors are in place. A strong consensus emerged that long-term testing is the most reliable method for understanding true radon exposure.

Open Comments

Participants in the radon working group offered several key insights in their open comments. They highlighted the importance of differentiating between passive and active real-time radon monitoring, suggesting that continuous real-time monitoring offers advantages in calculating exposure and assessing mitigation effectiveness. A strong emphasis was placed on the need for clearer guidelines on radon remediation solutions, particularly regarding ventilation and the calculation of airflow rates for various mitigation strategies. The carcinogenic nature of radon gas was reiterated, and a recommendation was made to adopt the term “reference level” instead of “limit” for consistency and clarity.

Ventilation Working Group

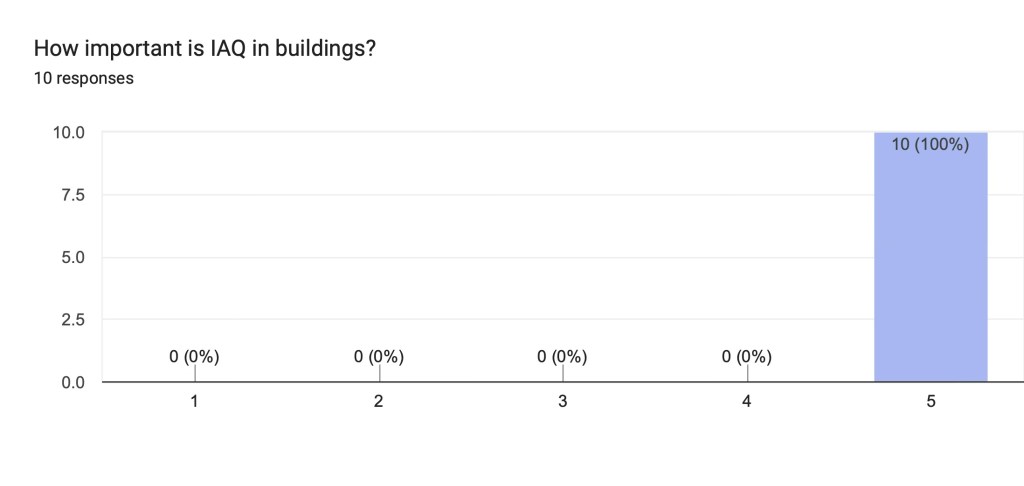

1st Question

The ventilation working group, with 10 out of 32 registered members participating, collectively agreed that Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) should be given the highest importance in buildings. This consensus underscores a strong collective belief in the critical role of IAQ in safeguarding occupant health and well-being, highlighting its prioritization above other building considerations.

2nd Question

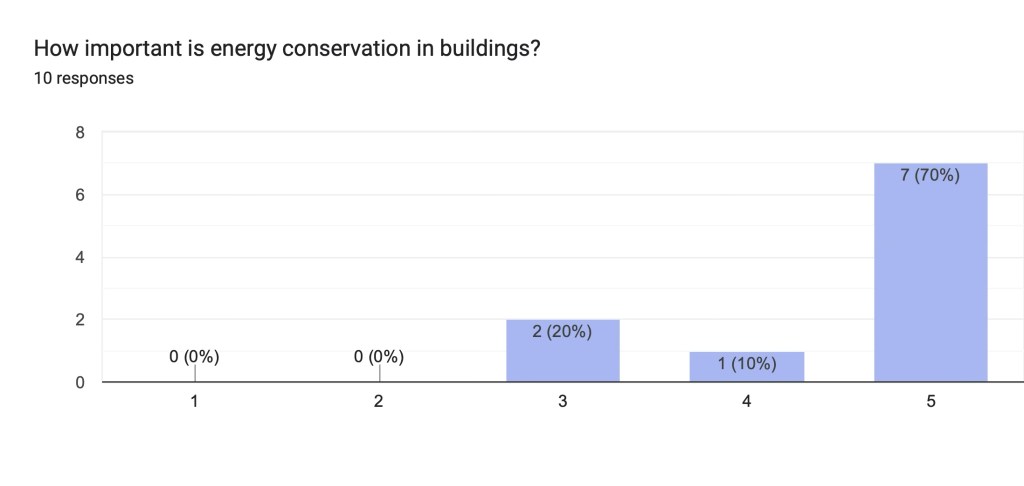

The ventilation working group, when considering the importance of energy conservation in buildings, revealed a strong emphasis on its significance. A substantial 70% of participants agreed that energy conservation should be assigned the highest importance, reflecting a prevalent commitment to sustainable building practices. While a notable 20% deemed it of medium importance, and 10% rated it as higher than medium, the overwhelming majority clearly prioritized energy efficiency, demonstrating a strong alignment with environmentally conscious building design and operation.

3rd Question

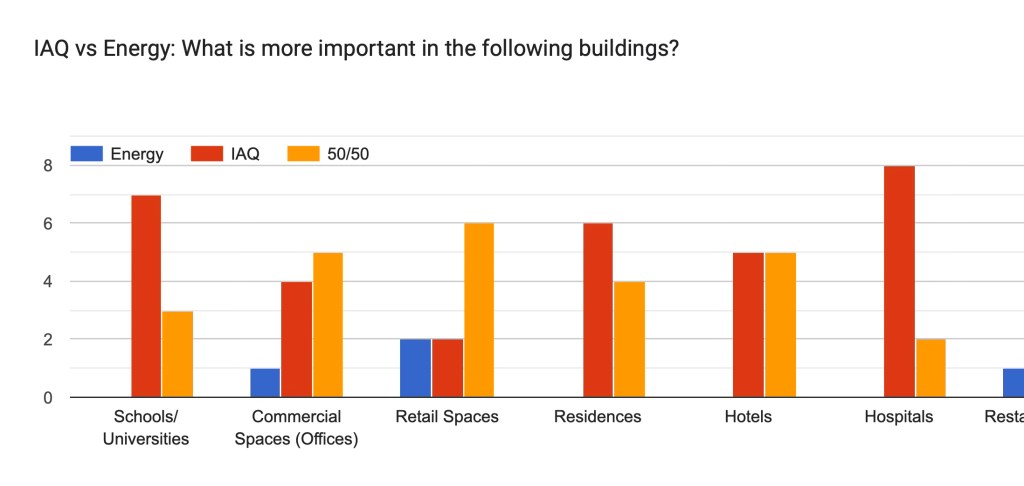

The ventilation working group’s evaluation of IAQ versus energy conservation across various building types revealed important priorities. In schools and hospitals, IAQ was predominantly favored, reflecting the critical need to protect vulnerable populations. Residences also leaned towards IAQ prioritization. However, in commercial, retail, and restaurant/café settings, a balance between IAQ and energy conservation was more commonly preferred, suggesting a recognition of both health and operational efficiency. Hotels presented an even split, with equal emphasis on IAQ and a balanced approach. These results underscore the context-dependent nature of prioritizing IAQ versus energy conservation, with a clear trend of prioritizing IAQ in spaces occupied by sensitive groups, while seeking a balance in commercial and public settings.

4th Question

The ventilation working group explored various strategies to increase Air Changes per Hour (ACH) in buildings while minimizing energy impact. Participants highlighted the importance of air purification that doesn’t produce pollutant by-products, such as ROS or oxygen-free radicals. A third approach, beyond filtration and hourly renewals, was proposed: air purification to reduce internal pollutants, thereby lowering the need for outside air and filtration.

The group emphasized the need for HVAC units to pass rigorous seal tests and for filtration systems to be modified to reduce pressure drop. They suggested using additional filtration systems and adopting fan motors with improved performance curves. The idea that filters save energy was challenged, with the argument that lower pressure is the key factor. Central air handling units and heat exchangers were recommended.

Three main strategies were identified: heat recovery ventilation systems, demand-controlled ventilation, and the use of frequency inverters or EC motors. Smart air quality sensors were proposed to adapt ACH based on occupancy levels. Free-cooling and geothermal ventilation were discussed, along with the importance of energy recovery, especially in climates where it’s cost-effective. The need to filter outside air, even with free-cooling strategies, was noted due to potential contamination.

Additional strategies included cross-ventilation, decentralized ventilation units, mixed-mode ventilation, ceiling and exhaust fans, and dual-path filters. Balancing outdoor air intake with internal recirculation based on sensor data was suggested. The use of controlled mechanical ventilation (CMV) and energy recovery ventilators (ERVs and HRVs) to increase ventilation with minimal energy impact was highlighted.

Furthermore, the group discussed the importance of considering differences in construction and political decisions that influence ventilation strategies. They emphasized the need for common limits and measurement procedures, as well as better-defined remediation solutions, particularly those related to ventilation.

5th Question

The ventilation working group highlighted that gas contaminants significantly influence required ACH rates, with VOCs being a primary concern, especially in public buildings. Participants noted that current IAQ monitoring often reveals high TVOC concentrations, as equipment is primarily designed for residential settings. Accurate VOC assessment requires laboratory analysis to rule out hazardous levels. While CO2 was deemed less problematic, with levels up to 5,000 ppm considered acceptable in the absence of other pollutants, the group emphasized that both external and internally generated contaminants necessitate careful monitoring and control.

The group stressed the importance of adhering to EPA and OSHA standards, advocating for the filtration of pollutants entering through “Fresh Air Requirements.” They also highlighted the need for localized monitoring, as emissions from neighboring buildings can impact IAQ. Increased ACH rates were recommended for higher contaminant concentrations. The group emphasized that certain gaseous pollutants, like VOCs and radon, are often more concentrated indoors, requiring dilution through increased ventilation.

Participants expressed concern that current ventilation practices often focus solely on CO2, potentially overlooking other harmful VOCs. They advocated for more comprehensive testing and research to establish ventilation rates based on multiple contaminants. The group also discussed the limitations of current ventilation methods, such as assigning fixed airflows per person, and called for more dynamic and responsive systems.

Furthermore, it was stated that higher contamination levels demand more ACH to dilute and remove excess pollutant. CO2 and VOCs should affect the ACH that may be modulated dynamically. TVOCs usually is 70–90% higher in the absence of controlled mechanical ventilation (CMV). VOCs are always present and should impact the ventilation rate but to what degree is difficult to quantify due to their presence, amount, varies affects (if known) on IAQ. When discussing ACH it is needed to address VOCs with this unknown in mind.

6th Question

The ventilation working group discussed several advancements in ventilation technologies aimed at optimizing ACH and improving IAQ. Participants highlighted the use of purely physical air purification systems, such as non-dielectric electrostatics, for trapping particles and degrading VOCs without harmful byproducts. Concerns were raised about listing specific technologies due to potential misuse in inappropriate applications, with bipolar ionization serving as an example where uncontrolled use could lead to increased particle concentration at floor level.

The use of air purifiers was generally recommended. Soft bipolar ionization, certified for the absence of ozone and byproducts, was cited as an effective method for eliminating contaminants and pathogens. Concerns were raised about other technologies, such as PCO, potentially generating harmful byproducts like acetaldehyde or releasing titanium dioxide nanoparticles.

Several advanced ventilation technologies were identified, including smart ventilation (IoT integration), advanced filtration technologies (HEPA, electrostatic precipitators), energy recovery ventilation, demand-controlled ventilation, and hybrid ventilation. The use of combined high-efficiency and low-pressure drop filters, heat recovery ventilation with enthalpy cores, and dynamically used carbon filters were also mentioned. The integration of sensors to switch filters and balance ventilation systems was highlighted. Additionally, HEPA and activated carbon filter systems in CMV, as well as energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) and heat recovery ventilators (HRVs), were noted as beneficial advancements.

7th Question

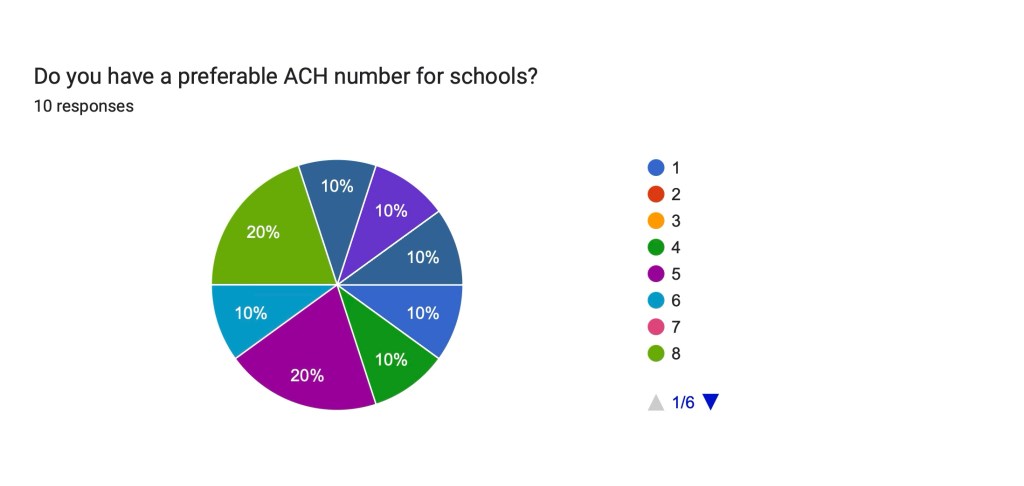

The ventilation working group’s discussion on preferred ACH numbers for schools revealed a lack of consensus on a specific value. While individual responses varied, the majority of participants suggested ACH rates ranging between 6 and 8. However, it is important to note that all participants gave an average number of 10 ACH, which indicates that while their preferred number was lower, they understood that a higher average of 10 was also acceptable. This indicates that while there is not a clear agreement on a specific number, there is a general understanding that higher ACH rates are better.

8th Question

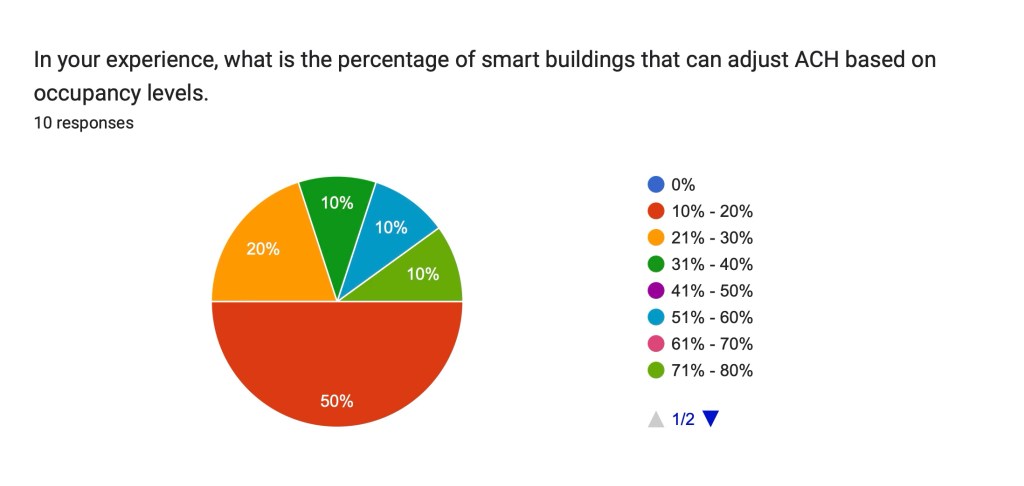

The ventilation working group’s assessment of smart building capabilities for ACH adjustment based on occupancy levels indicated a generally low prevalence. The majority of participants, specifically five respondents, estimated that only 10-20% of buildings currently possess such smart air quality integrations. While there were some outliers, with a few participants suggesting higher percentages ranging from 21-30%, 31-40%, 51-60%, and even 71-80%, the consistent clustering around the 10-20% range suggests that dynamic ACH adjustment based on occupancy remains a relatively uncommon feature in contemporary building infrastructure.

9th Question

The ventilation working group’s responses regarding followed ventilation standards revealed a reliance on established guidelines, with ASHRAE standards, particularly ASHRAE 62.1 and 62.2, being frequently cited. European standards, such as UNE-EN-16798-1 and UNE-EN-171340, were also mentioned, alongside the more recent ASHRAE 241. In Spain, participants referenced RITE, CTE, UNE-EN 16798, the Passivhaus standard, and RD 486 (PRL) with its application guide, as well as VLA limits for industrial settings. One participant indicated a focus on maintaining building design specifications rather than adhering to specific standards. This diverse range of responses highlights the varied regulatory landscape and the importance of considering both national and international standards in ventilation design and implementation.

Open Comments

The open comments from the ventilation working group revealed key insights into the complexities of achieving optimal indoor air quality (IAQ). Participants emphasized that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to ACH, especially in schools, is inappropriate. They argued for a tailored approach, calculating ACH based on specific building characteristics, occupancy, and pollutant levels. Concerns were raised about the tendency for building owners to prioritize energy savings over IAQ, particularly with variable speed drives, highlighting the need for AI-driven solutions to dynamically adjust ACH based on real-time IAQ data. The importance of proper filter selection and preventative maintenance was stressed, as even high-quality filters cannot compensate for poorly sealed systems.

Furthermore, participants criticized demand-controlled ventilation systems based solely on CO2, advocating for a more comprehensive approach using advanced sensors to monitor various pollutants like PM and VOCs. The discussion on schools highlighted the need for increased ventilation in environments with young children, due to their vulnerability, while acknowledging the economic implications. The importance of good IAQ in educational settings was reiterated, emphasizing its role in supporting learning and development. The group also addressed the limitations of current “smart” buildings, emphasizing the need for robust maintenance policies to ensure these systems function effectively. In essence, the comments underscored the need for a dynamic, data-driven, and context-specific approach to ventilation, balancing energy efficiency with occupant health.

Filtration Working Group

1st Question

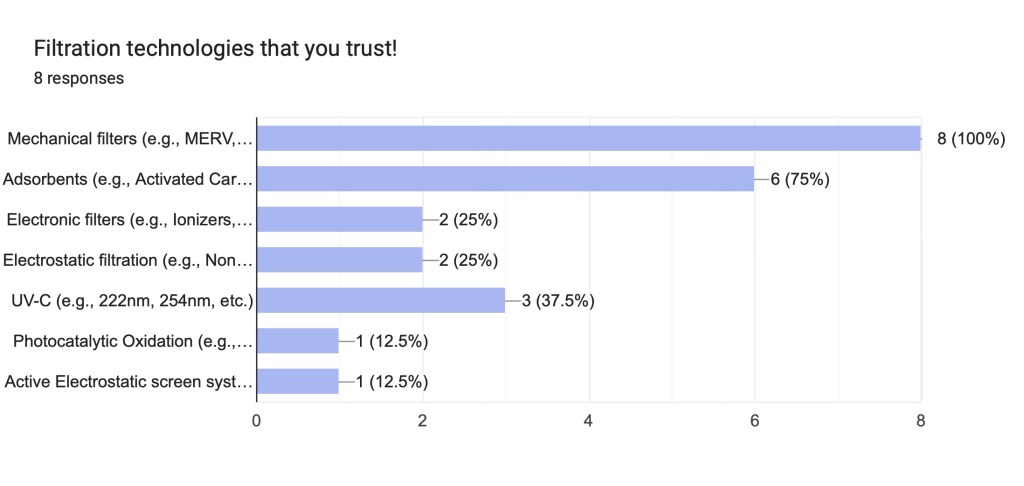

The filtration working group, with 8 out of 29 registered members participating, revealed a clear preference for established mechanical filtration technologies. All participants trusted mechanical filters like MERV, EPA, HEPA, and ULPA. Adsorbents, particularly activated carbon, were also widely trusted, with 6 participants endorsing them. Electronic and electrostatic filtration methods received moderate trust, with 2 and 3 participants respectively, indicating some reservations or a more selective application. UV-C technology, particularly 222nm and 254nm, was trusted by 3 participants, while photocatalytic oxidation received only single endorsement. This distribution suggests a strong reliance on well-established physical filtration methods, with cautious adoption of newer or more complex technologies.

2nd Question

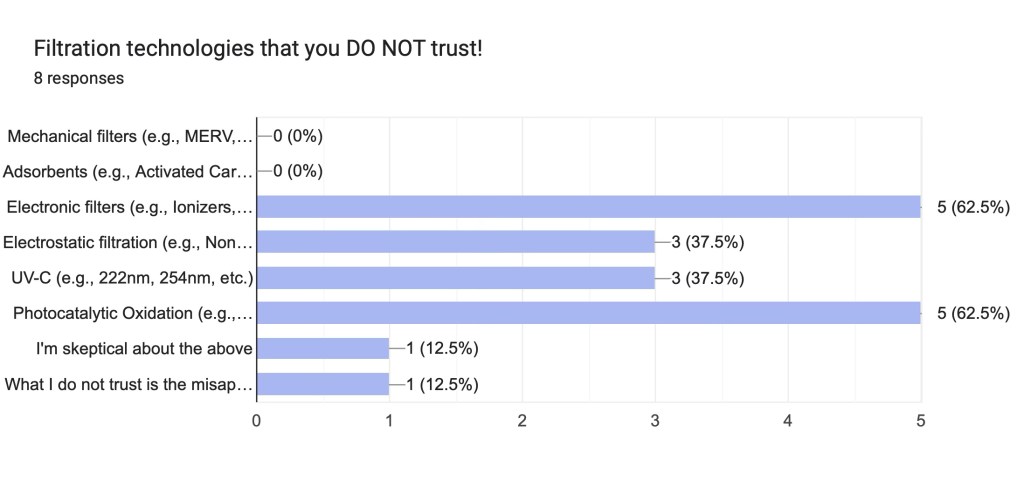

The filtration working group’s responses regarding untrusted filtration technologies revealed a clear skepticism towards certain methods. Notably, no participants expressed distrust in mechanical filters or adsorbents, indicating a strong confidence in these established technologies. However, electronic filters and photocatalytic oxidation were each distrusted by 5 participants, suggesting significant concerns about their efficacy or potential drawbacks. Electrostatic filtration and UV-C technologies were distrusted by 3 participants each, indicating a moderate level of skepticism. Beyond specific technologies, participants expressed general distrust in the misapplication of filtration products and the “one-size-fits-all” mentality prevalent among some filter experts, emphasizing the importance of context-specific solutions and careful application.

3rd Question

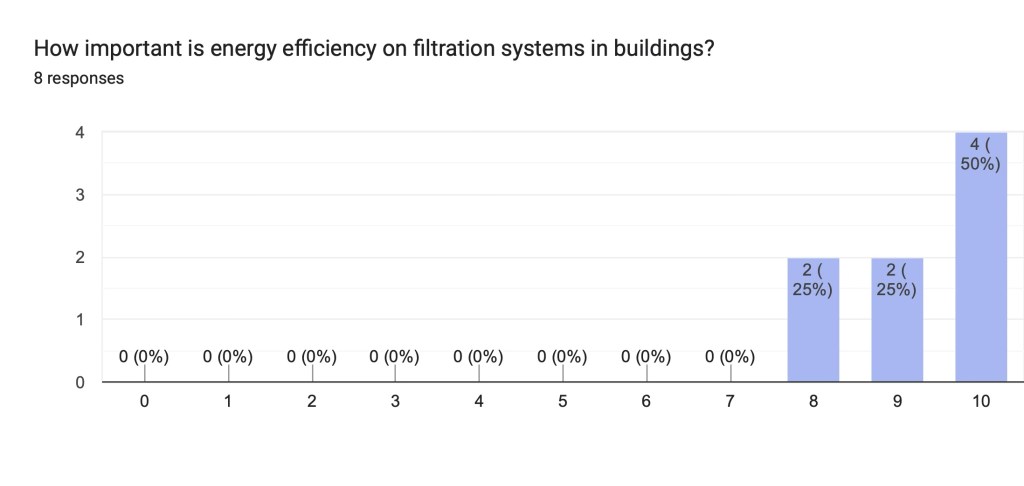

The filtration working group demonstrated a strong consensus regarding the importance of energy efficiency in filtration systems. Half of the participants considered energy efficiency to be “very important,” while the remaining participants also placed it within the highest range of importance. This unanimous agreement highlights a clear recognition of the need for filtration systems that effectively balance air purification with minimal energy consumption, reflecting a shared commitment to sustainable building practices.

4th Question

The filtration working group, focusing on energy-efficient removal of outdoor PM from indoor spaces, coalesced around several key strategies. Mechanical filtration and demand-controlled ventilation were consistently recommended. A strong emphasis was placed on source control, with participants advocating for preventing pollutants from entering the breathing zone in the first place, aligning with ASHRAE 101 principles. They also suggested a targeted approach, reviewing ingress routes and utilizing HVAC or portable solutions based on the specific areas affected. Combining mechanical filtration with other technologies, such as bipolar ionization, was seen as a promising approach for efficient filtration with reduced energy consumption. In mechanical ventilation systems, in-duct filters were preferred, while portable air cleaners were deemed appropriate for naturally ventilated buildings. Across all recommendations, the group stressed the importance of third-party testing to ensure that filtration technologies do not produce harmful byproducts, like ozone, and to validate their overall effectiveness.

5th Question

The filtration working group, when addressing indoor PM removal from internal sources, emphasized mechanical filtration as a primary strategy. Maintaining humidity and using air purifiers were also suggested. Preventing PM from recirculating into the breathing zone was highlighted, with recommendations for high CFM and the highest possible MERV value filters, particularly focusing on particles under 1 micron as per ASHRAE 52.2 E1 standards. The group discussed filter blow-through percentages, emphasizing the importance of high MERV ratings for effective removal of 0.3-1 micron particles. Personal experiences with high-MERV filtration systems, including pre-filters and continuous blower operation, were shared to demonstrate effective and long-lasting performance. Portable solutions, such as freestanding HEPA units, were recommended for localized PM sources. Opening windows, combined with filtration and mechanical ventilation, was also suggested. Bipolar soft ionization, when certified to not produce ozone or byproducts, was considered a highly effective active system, as it moves with the air and addresses the limitations of passive filtration systems.

6th Question

The filtration working group’s discussion on removing gases from indoor spaces through filtration revealed a preference for activated carbon and adsorbents. Concerns were raised about photocatalytic oxidation (PCO) due to potential harmful byproducts and titanium dioxide particulate matter release, necessitating high ventilation rates. Participants emphasized the need for third-party testing to validate the filtration capacity of activated carbon and other methods. A combination of activated carbon with soft bipolar ionization was suggested as a potentially effective approach. Ventilation was also mentioned as a key strategy. Some participants strongly cautioned against using carbon media for IAQ, recommending chemisorption filtration and increased air exchange instead. The complexity of gas removal was acknowledged, with the efficacy depending on various factors, including the specific pollutant and its source. The need for more research and standardized evaluation methods was highlighted, with initiatives like COST Action Net4CleanAir recognized as valuable contributions.

7th Question

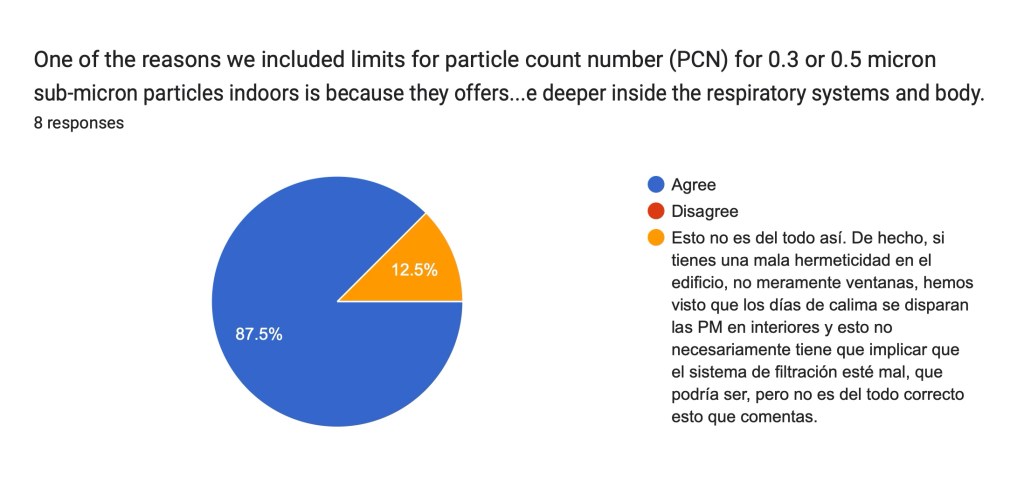

The filtration working group, with a strong majority of 7 out of 8 participants, agreed that incorporating particle count number (PCN) limits for 0.3 or 0.5 micron sub-micron particles provides valuable, low-cost insights into filtration efficiency, especially in identifying common HVAC system issues. They recognized PCN monitoring’s ability to offer real-time feedback on filter performance, crucial for timely interventions like filter replacements or system repairs, thus ensuring healthier indoor air. However, one participant argued that a rise in indoor PM levels, particularly during haze events, doesn’t always indicate poor filtration, but could also be attributed to poor building airtightness, highlighting the importance of considering multiple factors when interpreting PCN data.

Open Comments

The open comments from the filtration working group revealed several key considerations for effective indoor air quality management. Participants emphasized the critical importance of system-wide sealing in HVAC systems, advocating for a new “System 52.2 Seal” certification to ensure that even the best filters perform optimally. They highlighted that without proper system sealing, IAQ efforts are significantly compromised.

“Trust” in filtration technologies was linked to factors like long-term reliability, manageable maintenance, dependability, and the impact of soiling on performance.

The group acknowledged the current state of research on air cleaning and filtration, noting that while PM filtration is relatively well-understood, the literature on gaseous and biological compounds is scattered and limited. They stressed the importance of relying on robust scientific evidence when making recommendations, particularly in the GO AQS White Paper and website. Caution was advised against endorsing technologies with potential harmful byproducts, such as ozone-producing ionizers, if robust data does not support the technology.

Finally, participants recognized the role of filtration in helping companies reduce their carbon footprint by effectively removing particles from the air, rather than simply diluting them. This highlights filtration’s contribution to both IAQ and sustainability goals.

What’s Next

Following the collation of results from the working groups, we are now entering the next phase of finalizing the Global Open Air Quality Standards. Participants will be granted a 10-day window to submit any additional comments or feedback. Subsequently, we will schedule virtual meetings to facilitate in-depth discussions and address any remaining concerns. These meetings are designed to ensure a comprehensive and collaborative approach, ultimately leading to the finalization and implementation of the Global Open Air Quality Standards.

Leave a comment